Respectful Discourse and Getting to the Heart of Matters

Watching how disrespectfully my views are treated by the Woke world since my cancelation has made me think more carefully about how I can be more respectful, myself, when I come up against arguments that it is my first instinct to ridicule or dismiss.

So I caught myself the other day when I read a bunch of Twitter posts about how what the World Economic Forum, Justin Trudeau and Kamala Harris believe in something called “climate communism.”

Now, if I were simply interested in contradiction and dismissal and not engaging, this essay would be about how it strikes me as weird that rule by the super-rich and massive state subsidies to fossil fuel companies to build pipelines, fund oil exploration and subsidize natural gas liquification constitutes “climate communism.”

Isn’t communism about the government shutting down corporations and socializing assets, not buying presents for big companies the way the Canadian government did with the TMX pipeline or handing out six billion dollars in subsidies to Royal Dutch Shell, Petronas and other big oil companies as the BC government has done? Also, isn’t communism about government officials running our lives not Mark Zuckerberg, George Soros, Bill Gates and other unelected billionaire CEOs running them from outside the government while the state looks on passively?

But the reality is that most of the people who are worried about communism on the internet these days believe that it means what “fascism” used to mean: a cabal of state and private corporate actors, led by the super-rich, shutting down democracy and immiserating and impoverishing the populace.

And these days, our terms are so mangled that, for people like BC premier David Eby, increasing natural gas and petroleum emissions, extraction and exploration is climate action. For many, “climate action” has come to mean flying private jets everywhere and building gigantic coal-fired server farms while punitively taxing people who drive to work because their bus route has been shut down by the government and they are driving a used car and not an EV they couldn’t afford.

There are lots of problems with our mangled language, a feature of the Newspeak of the Gaslightenment. But what if we instead focused on the truth words might be unexpectedly freighting too?

When I began writing this essay, it was largely to explain, just more constructively, why the term “climate communism” made no sense. So, I began writing my typical style of essay, based on my training in the method and theory of the history of ideas. And, as I chronicled the various debates in ecopolitics since the 1970s, I came to realize that the term does point us towards knowledge and intellectual clarity, that while not literally true, it is nonetheless informative.

But to understand how, it is necessary to head back to the closing years of the eighteenth century.

The First Economic Materialists

I am going to start this story in 1798 with the publication of An Essay on the Principle of Population by economist Thomas Malthus. Contrary to the claims of orthodox Marxists, Malthus’s book was the first work of structuralist, materialist history in the West.

Malthus’s argument was that human societies had a natural boom-bust cycle structured primarily not by immaterial ideologies or beliefs, not by institutional systems for organizing political or labour power but instead by human reproduction and the physical environment in which societies are located.

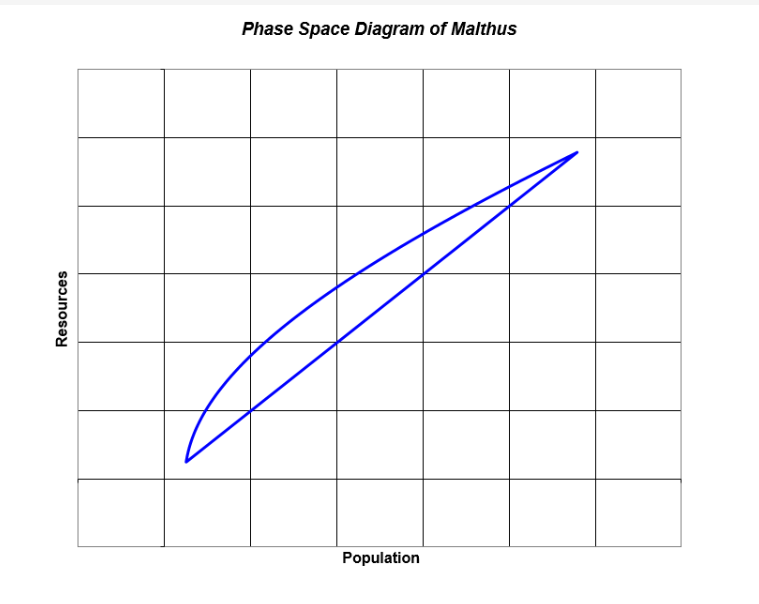

Malthus argued that human societies in a state of material surplus, with respect to food and energy, tend to grow until the population does not merely hit a limit where it consumes all the calories it is producing and there ceases to be surplus; it will overshoot that surplus, resulting in famine and other associated morbidities that will act to push population levels back down to a level at which surplus can again be generated. And this cycle will repeat indefinitely.

In other words, history has a shape, a pattern, based on the physical limitations of the material world. If one were to graph human action in time based on Malthus, history would look something like this:

It was Malthus, then, not Karl Marx who first put forward a theory of history patterned and structured based on material reality. Malthus, not Marx, was the first “historical materialist” who looked past the military and political history of “great men” and saw a more profound and durable pattern arising from material realities of food production and the beginnings of a concept of an ecological footprint. It is Malthus who gave us the intellectual equipment for the idea of an “earth overshoot day,” now an important piece of ecological thought.

Writing before the fossil fuel revolution fundamentally altered the energy calculus of human civilization, Malthus’s understanding of human history was of a basically cyclical history orbiting around a steady ecological state.

Fifty years, later, when penning the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx argued for a different theory of history, one that, while deeply concerned with the materiality of human labour and associated technologies, the corpus he and Friedrich Engels generated in the ensuing decades was strangely devoid of any serious analysis of the ecological impact of the labour and technological regimes it discussed.

Even as organizations like the Sierra Club began to coalesce, even as major health and ecological damage became evident from the impacts of expansion of coal-fired industry, Marx and Engels largely handwaved this. Once the workers controlled the factories, naturally, they would manage them in a way that did not degrade human health or the environment.

Indeed, if we were to graph Marx’s theory of history, as I did a decade and a half ago, we can even the inflationary, expanding character of human societies and economies as history approaches its crescendo. Marxism may be materialist in the sense of labour systems but not in the more conventional sense of the term. Despite the first “limits to growth” theory preceding Marxism by half a century, no serious environmental insights inform an otherwise brilliant analytical corpus.

The Marx-Malthus Debate Arrives More Than A Century Late

While Marx and Malthus clearly put forward adversarial theories of history, no Marx-Malthus debate appeared in the nineteenth century or most of the twentieth. For one thing, while the Marxist corpus and its vast array of fanfic were selling like hotcakes, Malthus gathered dust on the shelves. It seemed that fossil fuels, chemical fertilizers and new industrial agricultural and fishing technologies had rendered Malthus obsolete, at best, and, at worst, dead wrong.

But, beginning in the 1970s and rising to a crescendo at the end of the 1980s, positive reappraisals of Malthus began as the Green Revolution in chemical agriculture began delivering adverse health effects and long-term environmental degradation, as the consequences of fossil fuel extraction and emissions began clearly showing their long-term costs, as wild fisheries began to collapse.

And beginning with the publication of Small Is Beautiful by E F Schumacher in 1973, a new corpus of writing emerged within which there would finally be a serious intellectual confrontation between Marxian and Malthusian thought. Ecopolitical philosophy was, for a generation, a vibrant and dynamic field of serious intellectual debate, something hard to remember, given the rapid and shocking de-intellectualization of the environmental movement and of Green parties over the course of the 1990s.

Broadly, ecopolitical philosophy organized itself into four camps: Bioregionalism, Ecofeminism, Social Ecology and Deep Ecology. With the exception of Ecofeminism, each of these ideological tendencies was either fully Marxian or Malthusian in its environmental approach. Bioregionalists and Deep Ecologists believed that Malthus was essentially correct, that ultimately, there were hard physical limits on human population and human activity and that while these limits might be deferred by technology or economic systems, this would simply delay and, consequently, intensify the environmental day of reckoning.

The expansion of industrial society and the increases in human population it made possible essentially entailed more radically exploiting natural resources and ecosystems, meaning that when civilization was finally stretched to far past its normal Malthusian limit, the scale of the inevitable collapse would simply be that much more cataclysmic. Deep Ecologists and Bioregionalists backed strategies to reduce population and economic scale, favouring local, self-sufficient economies, de-industrialization, elimination of the logistics industry, etc.

Deep Ecologists got into some hot water in 1984 when some movement leaders suggested that the Ethiopian Famine was a Malthusian population correction and seemed to show an indifference to famine aid. Especially damaged by this was the leader of Earth First!, Dave Foreman. But all Deep Ecologists were forced to confront a certain dark misanthropy that inevitably seeps into movements that attempt to de-centre human universality in their philosophical system. (That is not to say that such philosophies are illegitimate but simply that they come, like any school of thought, with a particular set of unavoidable problems that they must confront.)

Surprisingly, one person who came to the rescue of the Deep Ecologists was Murray Bookchin, the anarcho-socialist philosopher who led the Social Ecology movement. Unlike the Deep Ecologists and Bioregionalists, Bookchin joined the Marxists in effacing the very possibility of serious environmental problems existing in labour systems he deemed fair. Nevertheless, Bookchin agreed to engage in an epistolary debate with Foreman to seek common ground between their respective philosophical tendencies.

Of course, there was something in it for Bookchin. For some time, he had been using the term “Malthusian” as an epithet with which to attack Deep Ecologists. In his dependent position, Foreman was forced to disavow Malthus at Bookchin’s invitation in Defending the Earth, the book in which they published the exchange.

Presaging the contemporary left’s Newspeak linguistic orthodoxy, something enthusiastically practiced by Bookchin’s institute since his demise, Bookchin’s argument against Malthus was not an argument in the conventional Enlightenment sense. Rather, he put forward the view that Malthus’s original theory did not merely describe what he deemed possible but what he deemed desirable. According to Bookchin, Malthus as not a man warning us to avoid overdevelopment lest it cause widespread famine and disease but a man who celebrated famine and disease as a righteous punishment for the poor having too many babies.

Even prior to his debate with Foreman, Bookchin had sought to turn “Malthusian” into a blasphemous epithet connoting support for eugenics, population culs, etc. The moment anyone raised the possibility of limits to human population or the problems of stretching finite resources across a large number of people, Bookchin and his followers would declare their interlocutor a “Malthusian” and refuse to debate them on the grounds that they were basically the same as Hitler. “Malthusianism,” to Bookchin, was not a bad idea but a blasphemous one, one he would condemn rather than debating whenever it appeared to rear its head.

Belief in limits to growth and understanding scale to be, itself, the main ecological problem, generally won the day in ecopolitical debates from 1970-88. This was years before the Woke moment and, consequently, the Social Ecologists generally came off as haughty, censorious and bad-faith debaters. Until the late 80s, they were the intellectual and political outliers, often bringing a destructive sectarianism to Green political projects, further undermining their credibility within the larger movement.

But this changed with the United Nations’ publication of Our Common Future, by Gro Harlem Brundtland, the Prime Minister of Norway and chair of the UN Commission on Environment and Development, whose findings the text reported. While the commission did some excellent work in documenting and describing the “interlocking crises” (a useful term it coined), its overall effect was, in the view of many environmentalists, of whom I was one, anything but salutary.

In the view of Brundtland and her fellow commissioners, the primary cause of environmental degradation was not over-production or excessive wealth but the opposite. Overgeneralizing from the case of illegal forest clearance and desertification in the Sahel region of Africa, the commission advanced the view that poor people destroy the environment by doing desperate and unsustainable things and that the best way to stop this was to make the world much richer. Bizarrely, a report on the adverse effects of the rapid and dramatic expansion of industrial civilization, reported that the only way to turn the tide was to expand industrialization even more rapidly.

In fact, Brundtland’s recommendation that we dramatically accelerate the industrialization of the Global South so as to achieve a five- to tenfold increase in the size of the global economy was promptly echoed in Bookchin’s next book Remaking Society. This new belief in rapid industrial development as the solution to the world’s environmental ills caught on fast because it also had a sexy name. Brundtland called it “Sustainable Development.”

While some visionaries in ecopolitics like my mentor, David Lewis and Greenpeace founder and Stinger Missile designer Jim Bohlen joined me in denouncing the very idea of Sustainable Development, most of the environmental movement, including those interested in ecopolitical philosophy decided that the way forward was to treat Sustainable Development as a floating signifier and endorse it as a means of contesting its meaning in the public square.

Sustainable Development did not just prove a disastrous idea that sold the industrialization of the Global South as some kind of environmental remediation project; it also sounded the death knell of ecopolitical philosophy as a site of vibrant debate and critical thought. By the start of the twenty-first century, between the professionalization of the movement, through Blairite austerity and the decision to adopt a floating signifier as the centre of our master discourse, the environmental movement had self-lobotomized.

The movement’s leaders did not talk about the political thought of Marilyn French, Dave Foreman, E F Schumacher or even Murray Bookchin, for that matter. Green parties and the movements from which they had emerged had been absorbed into the, itself, rapidly debasing political discourse of the larger progressive left. And their reading material became that of the larger Progressiverse. When I asked a 2010s Green Party candidate what their favourite works of ecophilosophy were, they did not know any of those names but they did recommend the works of neo-Keynesian journalist Naomi Klein.

This is not to suggest the total destruction of ecopolitical thought. Derrick Jensen and his fellow thinkers in Deep Green Resistance, along with a few other courageous voices, continued the work of debating, speaking, thinking aloud about the big underlying issues behind the omnicide and the philosophical implications of addressing them. But, as much as I have compared him to Saint Jerome in effectively canonizing and rationalizing the creative cacophony that preceded him, an equally apt comparison is to the Teacher of Wisdom at Qumran. Because I fear the future of this work may be closer to that of the Dead Sea Scrolls than the Vulgate.

Climate Versus the Communists

At the beginning of the 1990s, as I have written elsewhere, the mainstream of the suddenly professionalizing environmental movement was not merely indifferent to climate as an issue; they were actively hostile. There were multiple reasons for this, some parochial, some universal. Certainly, direct bribes from the fossil fuel industry had something to do with it all.

But one important reason was that those of us in the movement who opposed Sustainable Development featured climate centrally in our arguments. Anyone with basic mathematical competence could look at a graph of the size of the global economy, tracking recessions, depression and booms and overlay a graph of carbon emissions and see that, for the past century or more, they have been basically the same graph.

The world economy ran on oil and coal and increasing its size meant accelerating the Greenhouse Effect.

The debate over sustainable development was the last gasp of the Marx versus Malthus debate and, sadly, the Marxists won. The environment was going to be protected by the fact that a planet on which everyone enjoyed, as Bookchin called it “bourgeois abundance” in Remaking Society would naturally become populated by educated, intelligent, conservationists. And such good, virtuous people would never hurt the environment.

Of course, the climate nihilism of 1990s environmental leaders could not stand indefinitely, especially following the Kyoto climate conference of 1997 when governments from low-lying nations of the Global South stepped forward as major voices for a growing global concern. But this did not result in some sort of continuity between the 1990s climate movement and that of the twenty-first century.

Those who had sounded the alarm on climate in the 1980s and 1990s found ourselves further marginalized as the Sustainable Development shills from blue chip environmental groups and government suddenly transformed into the leadership class of a new kind of climate movement, largely discontinuous with that which had preceded it, Greenpeace being a notable exception.

The New Climate Politics

Today’s climate politics bears scant resemblance to the activism in which I participated in the 80s and 90s. Back then, we used the term “Greenhouse Effect” because it had a pedagogical function because we felt that an educated public using their common sense was the way for us to make politics change. We made appeals to reason. Today’s movement makes appeals to authority, “trust the science,” “99% of scientists say,” “the science is settled,” have replaced “you know how a greenhouse works? Well…”

Instead of foregrounding how little we can predict how a destabilized climate will behave in future and how it is impossible to make long-range predictions about an enormous, complex, chaotic system like a planet’s climate, false discourses of control, combined with dubious mathematical modeling have given the world’s elite the sense that we can choose how fast and how much to warm the planet.

The debate between warming the planet 1.5 degrees and 3 degrees Celsius expresses a delusional fantasy of control, almost as detached from reality as climate denial itself. The synergistic cascading feedback effects of the atmospheric warming, oceanic hypoxia and ocean acidification that we have already unleashed are unknowable, never mind the effects of the inevitable substantial future carbon emissions.

Instead of spreading as much knowledge as possible and emphasizing how little we know about the future operation of weather systems and the carbon cycle, we have anointed a new priestly class. Experts on the articles of faith of progressives, epidemiology, climate and gender are persons of great knowledge so deep, so complex, that they could never explain it to you and won’t even try and, in fact, it may be impertinent to question too closely. They speak not for climate science but for “the Science.”

The reality is that most of these “experts” are not climate scientists, any more than the gender experts are geneticists or the public health officials are epidemiologists. Proper climate scientists these days are telegraphing panic and uncertainty, not narratives of social control, technological fixes and, mysteriously, insect-eating.

While climate might serve as a key justifying discourse for increasingly mechanized efforts at authoritarian social control, their private jets, coal-fired server farms, their obsession with concrete towers and subway tunnels show no particular interest in actually reducing carbon emissions. Indeed, it seems that whatever emission reductions the carbon austerity measures they impose on local populations achieve are quickly nullified by some new energy-intensive technology like AI, the building of another coal-fired electric vehicle factory or another war.

That’s because, like Marx and Bookchin, they are thinking like the governments of the USSR and People’s Republic of China. Chinese and Soviet steel mills produced steel as a biproduct in their effort to manufacture more communists. Similarly, our society’s commissars are trying to manufacture a new kind of person through new practices of social control, new technologies and a more totalizing labour system.

The measures they advance, from bossy electric vehicles to straws that come apart in your mouth, are focused only indirectly on the atmosphere. They are about making a new society, populated by a novel kind of human being, one whose citizens will then fix the climate. Their politics are based on a belief much like that of Marx or Bookchin that if you impose the correct material and labour conditions on people, they will become the sort of person human beings need to become.

And once that happens, the environment thing… it’ll take care of itself.