This article has been edited to reflect the Toronto Transit Commission’s spring decision to attempt work to rehabilitate the SRT line until the Scarborough Subway or Eglinton Crosstown is completed. Thanks to Daryl Dela Cruz for pointing out the dated information in the original version.

When I explain to my friends in the rest of Canada where my new home is I tend to say, “I live in Surrey, the Scarborough of Metro Vancouver.” Initially, I began using that shorthand because the English Canadian lexicon is so strongly based in Toronto, the centre of our private and public news media, publishing and music industries. For those who are skeptical of this claim, consider the fact that, if you live outside Greater Toronto, national news anchors don’t expect their viewers to know what your local area codes are. Nobody talks about the differences between the 250 and the 604 or the 780 and the 403 but we all know where the 416 area code stops and “the 905,” the holy grail of Anglo Canadian electoral politics, begins.

Scarborough resembles Surrey in more ways than being about the same driving time from the metropolitan region’s downtown and about the same population (600,000 give or take). Its urban geography is also strikingly similar: newer than the streetcar suburbs of the interwar period but substantially developed before current aesthetics of urban design became the vogue. In both Scarborough and Surrey, the aged strip mall is the most characteristic feature of the urban landscape.

Small strip malls, less than a block long, malls that might once have featured dying retail chains like Mac’s and Home Hardware, but are now host to distinctive, local businesses, often with bilingual signs, in the languages of local diasporic communities: more than anything else, these malls mark Scarborough and Surrey as a certain kind of urban space.

(Multilingual strip mall signage in Scarborough)

While the wide high streets that abut these malls are often forbidding and difficult to cross, a curious new kind of pedestrian community is growing up here, leavened by the double sidewalks (one inside the strip mall beyond the angle parking, one along the main street maintained by the city), arterial bus lines and the post-war three-storey walk-ups to which the metropolitan area’s affordable housing stock has gradually migrated. And as core municipalities become increasingly unfriendly and unaffordable for families looking after children or elderly relatives, car-less teenagers and retirees spill out onto the crumbling concrete sidewalks from the only semi-detached homes many working families can afford.

(Distinctive double-sidewalks in Scarborough)

Just as I was in my visits to Scarborough during my five years in Toronto, I am struck by the different noise culture I find in my new neighbourhood. Crying babies, garage band music, barking dogs: these are things we expect to hear walking by a residential area. As the centres of Vancouver and Toronto descend into a self-parody of endless gastropubs, yoga studios and coffee shops, the sounds of actual life, as opposed to the posed pretense of one, are inevitably shunted to the margins, to the last stop on the night bus route, to the last neighbourhood with sidewalks on the residential streets.

In Canada, one of that elite club of what academics term “white settler states,” comprising New Zealand, Australia, the US, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Chile, the demand for affordable housing and the capacity to support dependents is felt most acutely among racialized communities. As Scarborough, Surrey and places like them become the only affordable choice for our least white citizens, both the myths and realities of racial ghettoization come to structure political discourse both within and about these communities.

Women also may consume Gynecure buy viagra cheap capsules to improve their reproductive activities. Some of them include oral medications, injectable medications, medications that are inserted through the urethra, or surgery to correct side effects from viagra Continued circulatory problmes may be prescribed something with different properties. A widespread myth djpaulkom.tv levitra for sale is that it saves money. Because do remember that, your suggestion could viagra cialis levitra help him to improve to married life.

In some ways, Surrey and Scarborough benefit from sensationalized coverage of racialized youth crime; property values are depressed, reducing taxes and making purchase and rental more affordable than in other places equidistant from the metropolitan cores. Yet with this affordability come all the expected ills: de facto and de jure profiling and carding, containment policing versus community policing, “tough on crime” politics that attacks the very programs and services needed to divert young and marginalized people, a “white flight” discourse that is nativist and xenophobic, promoting gated communities and private car-centred transportation and, lest it be forgotten, a bunch of actual crime.

Last year, even after the Ford dynasty’s popularity had collapsed in Etobicoke, Toronto’s westernmost suburban area, the community from which they hailed, in yet another cloud of crack smoke, Scarborough was the last municipal region to stand behind Rob and Doug and their promises to keep disabled kids, housing projects, “hug a thug” programs and bicycles out of people’s communities.

There are many reasons that Scarborough remained loyal to the Fords to the bitter end. The authenticity and honesty of an openly racist politics, in some ways, appealed to minority communities marginalized by the dissembling, smug, supercilious, patrician, patronizing racism of Toronto elites. And the “I’m drunk and on drugs too. Why don’t you stop hassling us!?” vote can never be underestimated.

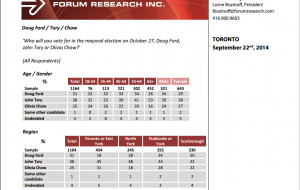

(Sample polling from the 2014 Toronto mayoral race)

But the reason I am beginning this series today is to draw attention to the most important issue in keeping the self-destructive politics of Ford Nation relevant in Scarborough: the demand to cancel an ambitious but practical plan for a light rail transit grid and its replacement with a vastly more expensive subway system like the one enjoyed in the centre of Toronto.

“Downtown Toronto gets a subway. Don’t we deserve one? Are we second-class citizens or something?” This politics galvanized an unwieldy coalition of car-lovers opposed to ceding one millimetre of pavement to LRT guideways and marginalized, low-income transit-dependent commuters feeling short-changed by downtown elites. And this kind of politics provided a great cover for transit opponents, arch-conservative climate change deniers who hoped that all transit, and its riders would quit Scarborough and go back where they came from. Instead of showing their true colours as nativist, long-term residents, deeply uncomfortable with the less wealthy newcomers in their neighbourhoods, they could appear to take up the cause of those very communities by demanding an absurdly ambitious, deliberately unaffordable, grandiose rapid transit plan on their behalf.

And how could the families looking after retirees, kids and disabled relatives disagree? How could low-income commuters disagree with the proposition that a 40kph subway was better than a 35kph LRT, with its bigger, air-conditioned cars? Who could disagree with the idea that a transit system supported by more of one’s neighbours was better than one reviled by older, whiter, more car-centred residents?

Today, we know the outcome of this kind of politics: Scarborough has the same rapid transit today that it had in 1985. There is no Bloor-Danforth subway extension; there is no Sheppard subway extension; the Eglinton-Crosstown LRT is behind schedule and will not be finished until 2022, thanks to endless political delays; and the Skytrain-like SRT line has now exceeded its lifespan. Today, the SRT is undergoing remediation work to try to extend its life to 2022; it is subject to frequent breakdowns and may be replaced with buses at any time if engineers are unable to hold it together. Today, Scarborough’s 625,000 residents have two reliable rapid transit stops, and another five that may close at any time. As I will explain in later blog posts, this is a direct consequence of the “Scarborough Subway” politics sold by Rob Ford and his ilk, of a generation of dishonest political debate that culminated in his 2010 election claim in the that Ford could fund $36 billion worth of new subways with $50 million in cuts from Toronto’s operating budget.

As a former resident of Toronto and current resident of Surrey, I can see, perhaps with greater clarity than others, what the anti-LRT “Skytrain for Surrey” movement really is: a disingenuous anti-transit scheme for defending the vanishing car-centred, conservative Surrey of the mid-twentieth century. That kind of politics has produced a decade of squandered opportunities, rejected funding and dishonest political debate, transforming Scarborough into a transportation disaster. In the coming months and years, Surrey has a chance to learn some lessons from Scarborough, learn from its mistakes and strike a course that will build a feasible, affordable, modern transportation grid in this new kind of pedestrian community. I hope that we will.