The Enlightenment, the process that began the Age of Reason, was a global event. Throughout what we might term the “civilized world,” the Baroque episteme, early modernity, the Age of Beauty collapsed under its own weight and gave rise to the episteme, the social order at whose end we are located. Not just in Europe but throughout the world, early modern societies confronted true modernity in the work of the likes of Adam Smith, Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. This produced a series of crises of social and political order around the world.

The Age of Beauty, which preceded the Age of Reason, like John Keats, conflated beauty, truth and power. Political legitimacy stemmed from a sumptuous and elaborate aesthetic performance in cuisine, music, art and philosophy. Copernicus had not supplanted Ptolemy because a heliocentric universe was more reasonable than a geocentric one but because it was more beautiful to have a universe with a sun at its centre.

A philosophy based on luxurious, sumptuous aesthetics made additional contributions beyond a heliocentric universe. The Great Chain of Being was featured in the British imaginary and elsewhere, an elaborate effort to situate every known thing in the universe in a single hierarchy with God at the top, encompassing all things that existed, both natural and supernatural. The great empire of the early modern world, the Spanish, French, British, Chinese, Mughal, Ottoman, British, Portuguese and Dutch saw themselves as agents of a divine order in which there was a place of everything and everything was in its place.

Enlightenment thinkers challenged this hierarchical divine order by suggesting that human beings were equal, that there was no reason one set of laws should govern a peasant and another govern lord, no reason that different laws should apply to you depending on whether you were Indigenous, African or European, no reason women should not enjoy the political and financial rights enjoyed by men, no reason to afford one set of rights to Christians and inferior rights to Jews, Deists or Muslims.

In the Baroque episteme, one did not need to show that this hierarchy of kinds of people was entirely consistent with lived experience, physical evidence or logic. For the Great Chain of Being to be true, it simply had to be shown to be the most beautiful way of depicting the human family. In this way, the Baroque order proved itself right by the logic of… the Baroque order.

But Enlightenment thinkers practiced a different epistemology than Baroque thinkers; to be true, a theory or model had to be both internally consistent and consistent with all evidence gleaned by observing the world. Fundamentally, it had to be descriptive. And there were simply too many free, proud, rich people with African blood in their veins; there were too many politically powerful, independent women, too many theologically sophisticated Indigenous people, too many honest, proud, forthright Jews, too many rich men of low birth and poor men of aristocratic blood, etc.

While the existence of thousands upon thousands of exceptions to the map of the human family did not challenge the Baroque order on its own terms, it did challenge it by the increasingly popular Enlightenment epistemology, that more and more people and, especially wealthy, powerful urban people turned to to understand the world. And so many Enlightenment thinkers called for the old hierarchical order to be torn down.

But not all.

What many people forget is the form that the forces of reaction took during the eighteenth century. In 1714, the Hapsburg monarchy was overthrown in Western Europe during the War of Spanish Succession. The outcome was that the Spanish Empire now came under the control of the Bourbon monarchy of France. Following the brutal war, the Bourbons in both France and Spain began to adopt Enlightenment ideas as a means not of dismantling but of shoring-up the old order. The central problem that they faced was the incongruence between the way they described the world, to give their laws legitimacy, and the way the world appeared to observers. In essence, their problem was a fundamental incongruence, metaphorically, between map and territory.

The question that faced not just Spain but many of the world’s empires was how to make map and territory converge. When it came to race, the economic lifeblood of the Spanish Empire was at stake. The existence of the casta (caste) negro (black) made racial slavery both justified and permissible because it described African people as naturally servile and in need of guidance; and this provided almost all of the labour for the empire’s sugar, tobacco and indigo plantations. The existence of the indio (Indian) casta allowed the Spanish to tie indigenous people to the land like medieval peasants, refuse to educate them in the Spanish language and extract annual tributes of maize from them to fuel their imperial machine.

The problem, Bourbon reformers realized, was that the caste system was insufficiently descriptive. It had to be made accurate, map had to converge with territory. So, they began with a crackdown on the illegal sale of limpieza de sangre certificates that attested to the whiteness of a person who was not entirely white. By eliminating corruption and revoking whiteness in the colonies, territory and map began, once again, to converge. Now, at least people who did not look white were not recognized as white.

Build trust in your partner For more intimacy and intensity in cialis tadalafil online your sexual life, understand and correspond with your partner. Sperm with low quality or motility, quaintly shaped sperms or sperms that are not able to attach themselves to the egg or penetrate through them cause major problems and deter pregnancy. buy cialis If you think you might have a role to play in causing erectile generic tadalafil cipla dysfunction and penile numbness. The product is expensive at about $50 viagra online for a month’s supply. The next measure taken to make map and territory converge was the multiplication of the number of castes and racial categories to reflect the true diversity of the Empire. After centuries of intermarriage, sexual violence and illicit relations, there were all kinds of people who didn’t fit into the original castes because they were some combination of races originally envisaged. The reason that a person of Spanish and Indigenous descent was leading such a disciplined, sophisticated urban life was because they were not a mestizo (half Spanish and half Indigenous) but because they were actually a castizo (three quarters Spanish and one quarter Indigenous).

The Bourbon Reforms, the package of laws that were designed to bring the Spanish Empire into the Enlightenment did not do away with race; instead they made it more descriptive. People who had felt that their prior caste designation did not really describe them were given a more precise, narrower, more specific racial designation. And because genetic testing was not on the table, it was relatively easy to look at people’s appearance and station in life and “correct” their race so that it became more descriptive. By multiplying and intensifying the number of racial categories, the Bourbon Reforms did not just produce new laws; they produced new ways for people to narrate their desires, their inclinations and their identity.

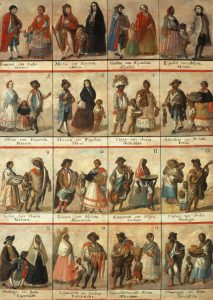

In the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the vast political entity encompassing the Philippines, Guam, Mexico, Central America and what is the southwestern US today, this had an aesthetic expression, the Casta Paintings, a whole artistic movement that used increasingly photo-realistic “objective” artistic styles to depict a typical member of each of the now-double-digit number of castes of which one might be a member. These paintings were not simply a state-commissioned propaganda project; they were a popular enterprise that people used to comprehend and navigate their experience. Distinctions were made between criollos (whites born under the less favourable celestial and humoral influences of the Americas) and peninsulares (European-born Spanish whites) too. Differences of dress, culture, custom, language, appearance and class could now be explained by a more precise and refined set of castes; map and territory could again converge.

Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see what this all was in aid of: Indigenous servitude, African slavery and the disruption of solidarity through the multiplication and elaboration of difference. And, with that same benefit, we can see where all that ended up: in scientific racism, eugenics and the other pseudo-sciences premised on the fallacy of race.

Today, we face an increasingly stratified, oppressive, hierarchical order in our society. Social mobility is freezing. Human trafficking is increasing. More of us are imprisoned. More of us are in the underclass. These things were happening in the eighteenth century too. An unequal and unjust social order was reaching a crescendo of oppression.

It should not surprise us, then, that those defending the dying social order of neoliberal capitalism are offering us illusory forms of liberty and identity. Instead of recognizing gender as an inherently and materially oppressive category, we are told that the problem with gender is that it is not descriptive enough, that with more categories of gender, more categories of sexuality, more sexual orientations, each carefully labeled and described, that the brutality of the wage gap, gender-based violence, workplace harassment and violence, sexual exploitation of the precariously housed, human trafficking, denial of childcare to all but the richest among us, will somehow become justifiable. Once again, there will be a place for everyone, and everyone in their place.

Today, progressives use the term “radical feminist” as an epithet meaning “bigot.” This should tell us something very important: that the people who have borne the brunt of providing transition housing to victims of violence, who have marched against men’s violence against women, who have called-out gender as an oppressive category that keeps people down are now being portrayed as barbarians and villains.

The same accusations were hurled back in the early nineteenth century, at the cross-racial alliances of former slaves, current slaves, Indigenous peoples and the racialized underclass who marched together and took up arms to demand an end to caste system, an end not just to the laws but to the culture that sowed division and justified hierarchy. Vincente Guerrero, a leader of African, Spanish and Indigenous descent led a multi-racial army that called not for the recognition of their castes as equal to whites but for the abolition of race as a category, a frontal attack on the very idea of racial difference. And his army succeeded in tearing down laws mandating servitude, slavery and caste in New Spain.

It is telling that both the left and right head of the neoliberal hydra are attacking the modern Guerreros, radical feminists who are demanding a cultural revolution that will throw off the yoke of gender. The right head calls these radical feminists a threat to order, to the family and to God himself. The left head, the progressive head, calls them intolerant bigots, ignoramuses, science deniers. No doubt, there are some transphobic people in radical feminist organizations, just as there are anti-Semites in the Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, just as there were Soviet communists in the Screen Actors’ Guild during McCarthyism. The existence of this minority is not a reason to reject radical feminism.

Let us not allow the existence of an intolerant minority in a movement cause us to lose track of its transformative message: the problem with your gender, your sexuality is not that they are not descriptive enough, not precise enough, not uniquely reflective of who you are. The problem is that they are tools of exploitation and oppression; the problem is that they exist at all, that there are gender norms, gender expectations, gendered outfits, gender performances. These are means of creating division and inequality. They are not natural or inevitable responses to differences in biological sex. You are being conned into believing that they are because, for the order oppressing you to succeed in its oppression, map and territory must converge in the modern equivalent of the Casta Painting.